A Correspondent:

The history of Bangladesh’s presidency is a significant component of the national narrative. Now that the country has its 22nd president in office, it makes sense to travel back over the terrain across which the office of president has come through the decades.

The presidency has enjoyed great, often unlimited authority. Again, the occupant of the office has been a figurehead, with limited authority and confined to a role which has not quite been conducive to the growth of a democratic culture in the country.

The presidency has in a couple of instances been commandeered by inordinately ambitious generals. In those instances, civilian presidents have been pushed aside by soldiers, their place taken over by generals who had earlier installed them in office.

It is all so very interesting. Bangabhaban, the official residence of Bangladesh’s president, has over the decades been witness to critical and crucial moments of national history, a story which often dates back to the period before the liberation of the country from Pakistani rule.

There has been all the drama enacted around the presidency, notably the moment when Supreme Court chief justice Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem was installed as president by General Khaled Musharraf on November 6, 1975. Sayem’s rise to the presidency followed the forced removal of Khondokar Moshtaque Ahmed from the office, one he had usurped through the assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman barely three months earlier.

Moshtaque was the very first usurper of power in Bangladesh, given that at the time of the coup in August 1975, he was minister for commerce in Bangabandhu’s government. Bangabandhu, it may be recalled, was between January and August of the year, in his second stint as the country’s president — and a powerful one at that.

The fourth amendment to the constitution conferred enormous authority on Bangabandhu, with the cabinet, though formally headed by Prime Minister M Mansoor Ali, conducting business on his authority. And, of course, the Baksal measure was another factor which ensured unlimited powers to the presidency as Bangabandhu presided over it.

Bangabandhu of course was the nation’s first president, a position legally conferred on him, despite his imprisonment in Pakistan, by the Mujibnagar government in April 1971. In his absence, vice president Syed Nazrul Islam, as acting president, carried out the responsibilities of the office till January 12, 1972.

On that day, Bangabandhu, who had come home a couple of days earlier, moved to a parliamentary form of government and assumed the office of prime minister. A consequently figurehead presidency went to Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury, who would occupy the office till 1973 before divesting himself of it.

Quite a good number of judges, driven by the mysterious configurations of Bangladesh’s politics, have served as president. Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury, Justice Sayem, Justice Abdus Sattar, Justice Ahsanuddin Chowdhury, and Justice Shahabuddin Ahmad are individuals who have left their imprints, significant or otherwise, on the office.

Justice Shahabuddin served in the office twice, first as acting president between the fall of the Ershad regime and the return of the country to a parliamentary form of government in 1991. He remains the only instance of a head of state to resume the responsibilities of chief justice of the Supreme Court before being elected to the presidency once the Awami League returned to power in 1996.

Both General Ziaur Rahman and General Hussein Muhammad Ershad retained a powerful presidency once they had seized the state in November 1975 and March 1982, in that order.

Zia installed Justice Sattar as vice president. On his assassination, Sattar took over as acting president and was then elected to the office in his own right in November 1981, defeating the Awami League’s Kamal Hossain. Sattar’s presidency was ended by Ershad’s coup. Justice Nurul Islam and Moudud Ahmed served as vice presidents under Ershad.

The presidency has often been a source of heartbreak for some of the individuals who have occupied it. AQM Badruddoza Chowdhury, raised to the office by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, soon found that he had sinned by not paying homage to General Zia at the latter’s grave. Chowdhury, among the founders of the BNP with Zia, was soon hounded out of the office by his party.

Moshtaque, who lost power in early November 1975, suddenly thought — and this was when General Musharraf’s coup collapsed on November 7, 1975 — that he had a good chance of returning to the office. That was not to be, for Sayem would stay on at Bangabhaban till April 1977, when Zia would force him out.

The Mohammadullah story is perhaps one that has not been replicated anywhere in global political history. He was speaker of the Jatiya Sangsad when he was catapulted to the presidency on the resignation of Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury in late 1973.

It was on Mohammadullah’s watch that a state of emergency was declared in the country in 1974. Not long after, he was succeeded as president by Bangabandhu, who then had Mohammadullah join the cabinet as a minister.

Meanwhile, Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury was appointed minister without portfolio by Bangabandhu on August 8 1975; and after the tragedy of August 15, Chowdhury took over as foreign minister when Dr Kamal Hossain, foreign minister under Bangabandhu, could not be persuaded to return home from abroad (where he had been on an official visit when Bangabandhu was assassinated).

Mohammadullah ended up, after August 15, as vice president under Moshtaque. He subsequently linked up with Zia’s BNP and under President Sattar became vice president. He lasted in the position barely 24 hours, for the Ershad coup sent the Sattar government packing.

In later times, Zillur Rahman, a close political associate of both Bangabandhu and Sheikh Hasina, was elected to the presidency. He was succeeded by Mohammad Abdul Hamid, a veteran politician and freedom fighter. Hamid’s tenure in the presidency, albeit shorn of the powers which once characterized the authority of the office, lasted a remarkable 10 years.

Not so remarkable was the presidency of the academic Iajuddin Ahmed. Having arrogated to himself the office of chief advisor in a caretaker government he formed in October 2006, he was unable to inspire confidence in the political opposition about his ability to preside over a fair and free election. The army forced him to give up the chief advisor’s office and so inaugurated a clean political slate in the country.

There has been at least one president who took bold action to uphold the country’s constitutional process. In 1996, as the nation prepared to go to fresh general elections, the army chief, General Mohammad Nasim, mounted what looked like a coup in defiance of presidential authority. President Abdur Rahman Biswas lost little time in sacking him and ensuring that the elections, supervised by the caretaker administration of Justice Habibur Rahman, went ahead.

Presidents of Bangladesh have been assassinated. Presidents who have lost power, notably Moshtaque and Ershad, have gone to jail on corruption charges. Men who would have made consequential presidents — Dr Kamal Hossain is an example — were unable to make it to the office.

There have been presidents who have been unabashedly partisan; other presidents have been colourless, working at the whims of their political parties. No woman has ever been elected to the presidency.

The powers of the office, as they used to be, are today severely depleted or non-existent. That makes one wonder. What legacy, if any, has Abdul Hamid left behind? The office is ceremonial, the icing on the cake of a yet-to-be durable democracy.

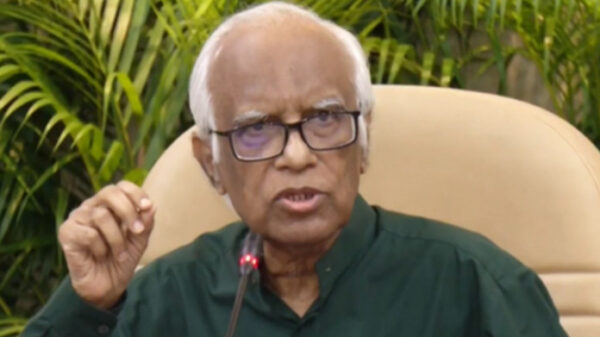

We will simply have to see what President Shahabuddin makes of the office which is now his to administer. It will be the expectation of citizens that he will reach out to all citizens, to persuade them into believing that he is president for every man, woman and child in Bangladesh.

That is a tall order. Even so, people will look to Shahabuddin to enrich and energise the office.