Staff Reporter:

During last year’s 29 July quota reform protests in Bangladesh, when the authoritarian Awami League (AL) government declared an official day of mourning for those killed, demonstrators rejected the state’s move and adopted an innovative form of protest instead: posting photos with red cloth tied around their eyes or faces and turning their Facebook profile pictures red.

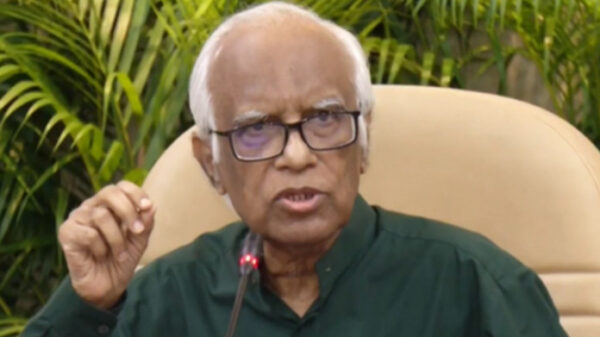

The story behind this unique protest was recently disclosed by SM Farhad, president of Dhaka University unit of the student organization Bangladesh Islami Chhatra Shibir.

Farhad recounted that at the time, when the state responded to what many described as a massacre by announcing dramatic national mourning and flying black flags, Abu Sadik Kayem approached him for advice.

“He asked me what we could do. I told him, let’s launch a counter-program. Since they are going with black, we should go with red,” Farhad recalled.

After he shared the idea, Sadik Kayem agreed, reportedly saying, “This could work. Let’s do it.” They quickly prepared a press release outlining the plan and sent it to protest coordinators, who then formally announced the program.

Farhad expressed surprise at the overwhelming response: “The next day, I saw people from all walks of life updating their Facebook profiles with red. Even Dr. Yunus and Khaleda Zia’s Facebook pages shared red profile images.”

Farhad explained the symbolism: “Since the state chose black, we thought we would choose red, the color of blood, as a way to protest the killings.” This led to the call for demonstrators to tie red cloths around their faces or eyes and update their social media profiles with red images.

He added that a key reason for choosing such an online “soft program” was the mounting arrests and lawsuits that followed more direct street actions. “Before moving to hard programs, we saw massive crackdowns with arrests and charges. So we decided to start with a soft program. If the soft program got a strong response, we planned to move to hard programs,” Farhad said.

When the red profile campaign gained significant traction online, it gave protesters renewed motivation. “The success of the red profile campaign motivated us. After that, we took to the streets. Our week-long soft program culminated in the red profile initiative,” he explained.

Farhad’s leadership during the uprising, as detailed in his own accounts, extended far beyond the red profile campaign. He played a central role in organizing blockades, hall protests, and coordinating both soft and hard programs, reflecting the depth of planning and determination that underpinned the movement.

This innovative online protest did not remain confined to the internet; it inspired a new wave of enthusiasm among demonstrators and encouraged them to mobilize on the ground in subsequent days